The Foundational Practice of Shamata or Calm Abiding

Meditation

In Tibetan the term for meditation means to familiarize yourself with something. When we meditate, we are familiarizing ourselves with our state of mind or a way of seeing things. Or becoming mindful of it, one might say. The normal state of our minds is unstable, scattered, easily distracted, and easily stirred up by thoughts and emotions. On a deeper level, our minds are unaware of the ultimate nature of reality. These are all states that cause us difficulty, stress, emotional pain, fear, anxiety, anger, and so forth. Most of us are drawn to meditation out of a yearning for peace and relief from these states.

Normally, we hold tightly to, identify with, and react to whatever thoughts, emotions, or feelings arise in our minds. Every time we do that, we reinforce habits that bring us pain and rob us of peace. We tend to chase what we think will make us happy and run from things we think will make us suffer. How exhausting! And in our chasing and running, we make a lot of messes for ourselves and others. When we time to meditate, we cultivate habits of seeing and relating to our own inner and outer worlds in a new way that bring us comfort and peace.

Shamata, Calm Abiding

On the Buddhist path, Calm Abiding serves as the foundation for all other practices. It is a technique used to develop our power of attention and bring our coarse and subtle thoughts to a restful state. In other words, it is resting or abiding in that peaceful state. We get a mini vacation from that chasing! The Nine Methods for Placing the Mind are used to develop that state of calm and single-pointed attention. Calm abiding can bring a powerful level of calm to the mind, so much so that one could rest for long periods of time without the slightest stirring of thoughts or emotions. Calm Abiding alone cannot eliminate our afflictive mental and emotional states or give us insight into the nature of reality.

As we move into the subsequent paths of practice such as Vipassana (Special Insight) meditations on selflessness, emptiness, and so forth, Calm Abiding serves as the stable ground on which we develop insight. It is not as if we develop Calm Abiding, then toss it as we move to further levels of practice. It integrates into whatever practices we do. When we practice Vipassana meditation on impermanence, the insight into the nature of impermanence is Vipassana or insight, while the mind’s ability to remain single-pointedly in that insight is Shamata.

Namchak Khen Rinpoche often uses the example of looking at something while rapidly blinking to show what Vipassana would be like without having first developed Shamata to a certain degree. We may get glimpses of insight into the nature of whatever object we are meditating upon, but that insight will be unstable and underdeveloped.

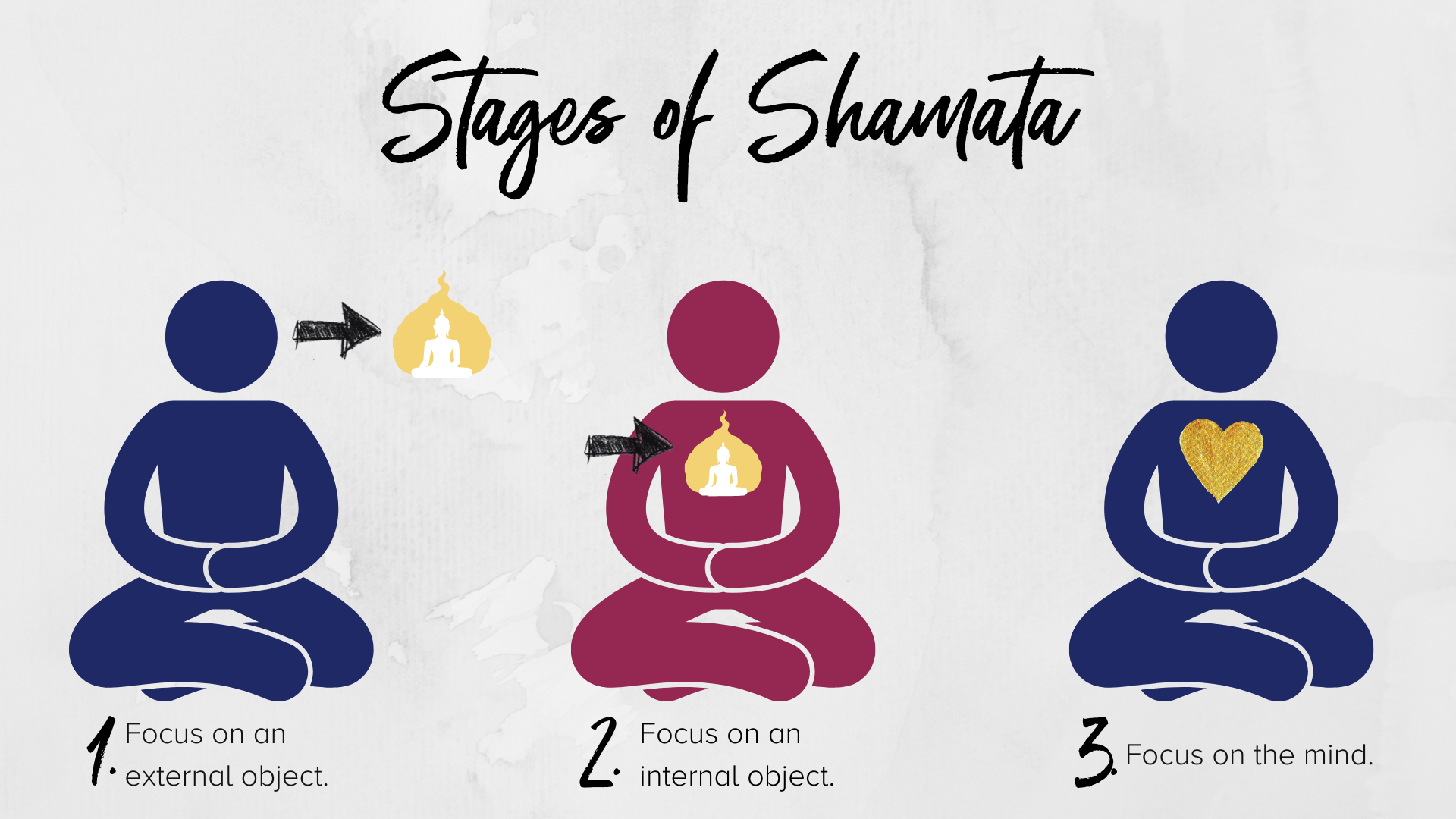

The Stages of Shamata

1. Focus on an external object.

When we begin in Calm Abiding practice, we start by focusing our minds on an external object, then progressively move on to an internal object, and finally drop the object altogether. The first step is the easiest because the object that we focus upon is external, coarse, and unmoving, like an image of the Buddha.

2. Focus on an internal object.

In the second stage, we move to an inner object. This is more difficult to maintain our focused attention, because the object is not physical. It is something that we imagine in our mind’s eye, and so it is more subtle, fleeting, and difficult to get in focus.

3. Focus on the mind.

Finally, we drop the object and focus upon our mind with our mind. This is usually when it is most difficult to keep our focus.

In order for our Calm Abiding to become a proper foundation for the insights of Vipassana, it is important to develop it through these stages. As we progress in our practice, we slowly gain freedom from that chasing after happiness and running from suffering.

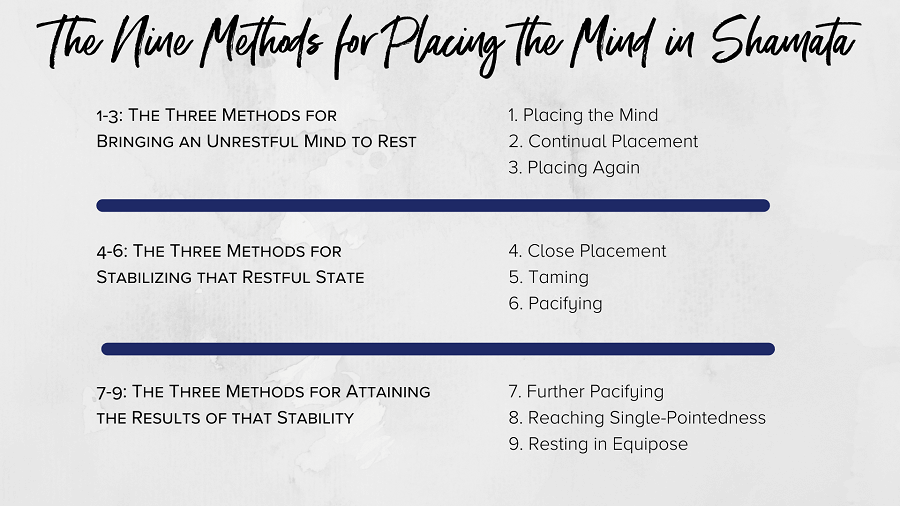

The Nine Methods for Placing the Mind in Shamata

How do we develop a solid foundation for our meditation practice? In the Namchak tradition, we follow nine methods. Depending on your experience and your mental activity that day, you may move through all these methods during one practice session. And some days you may end up focusing on the first three. These are also what Khen Rinpoche teaches during Shamata retreats. The Nine Methods are broken down into three groups of three:

The Three Methods for Bringing an Unrestful Mind to Rest

The first three of these methods help us learn to focus our minds upon an object. Normally, our attention is jumping around like a puppy dog, and we are very easily distracted. We increase our power of mindfulness when we notice our distraction and bring our minds back to the object. Then we can settle in with our object for more time without wandering off.

1. Placing the Mind: We begin by “placing” or focusing our minds on an object. In Buddhism, an image of the Buddha is most used. In that case, we focus our mind (which Buddhists see as being in the heart) to our eyes and our eyes to the spot on the Buddha’s forehead between the eyebrows.

2. Continual Placement: Here, we try to maintain our focus on the object for longer and longer periods of time without distraction.

3. Placing Again: As we are trying to maintain our focus on the object, we will get distracted. Here, we mindfully bring our minds back to the object again and again whenever they wander off. Whenever we notice that we’re distracted, we come back to the object and focus our minds on the object rather than the distraction. We avoid beating ourselves up or becoming self-critical for being distracted; simply notice and come back to the object. Thinking about thinking or thinking about our practice during our practice is more distraction. The more we do this, the longer we will be able to remain with the object without distraction, and we will more quickly notice our distracted thoughts when they do come up.

After our sessions, reflect and assess how quickly we were able to notice our distractions and resettle with our object. If things went well, rejoice and pat ourselves on the back! If not, we make a commitment to try and notice our distractions better next time.

The Three Methods for Stabilizing that Restful State

Because we improve our power of mindfulness in the first three methods, in the second set of the Nine Methods we further stabilize our meditation. We learn to overcome ever more subtle levels of thoughts and mental activity. Thoughts and emotions can be obvious, and because our minds are more stable we are more able to recognize and tame them.

4. Close Placement: Though we have developed our power of mindfulness and stability, we still get distracted, but not to the extent that we completely forget our object of meditation. When that happens, we strengthen our power of attention by continuously bringing our minds back to the object. Good news! There is no limit to the number of times you can bring your mind back to the object.

5. Taming: Here, we think of the benefits of meditation to keep us motivated. When we think on those benefits, it will help us to continue diligently on our path.

6. Pacifying: Here when thoughts come up, we remind ourselves that thinking is the cause of all of our difficulties, what keeps us from meditating. Thinking of these faults, we continue diligently focusing on our object of meditation.

The Three Methods for Attaining the Results of that Stability

Finally, in the last three stages, we overcome even the most subtle levels of thoughts as well as the faults of excitement, mental dullness, and laziness.

7. Further Pacifying: Continuing to apply effort in our meditation so that even the most subtle thoughts are pacified.

8. Reaching Single-Pointedness: As long as we apply the slightest effort, we can remain single-pointedly focused upon the object.

9. Resting in Equipoise: All mental agitation and laxity has been overcome, and we can rest in single-pointed meditative equipoise in a spontaneous manner with no effort required. Now doesn’t that sound peaceful?!

We can think of these Nine Methods as trail markers along the path.

How does Shamata help with Vipassana?

Calm Abiding is not the destination, but a crucial first step in our path of meditation. In the Buddhist tradition, once one has reached a stable level of Shamata, they’re considered ready to begin their Vipassana training.

The object of our Vipassana meditation is a mental object. It is an insight or a view of the reality of selflessness, emptiness, and so forth. That means that the object is very subtle and quite difficult to maintain in your mind’s focus. Read more information about Vipassana on our Vipassana guide page.

Shamata alone cannot eliminate all our mental and emotional afflictions. It puts them into a state of sleepy dormancy. If we were to stop meditating, all of them would awaken, and we would be right back where we started. It’s like mowing the weeds instead of pulling them out. They’ll pop up the next time it rains.

Alternatively, without Calm Abiding, Vipassana would be more like a flicker of insight that could not serve as an antidote to our afflictions. Vipassana proceeds through the stages of understanding, experiencing, and realizing. That initial flicker of insight is our understanding. Merely intellectually understanding that things are impermanent is not enough to eliminate our grasping at the seeming permanence of things. We need to familiarize our minds with impermanence and rest our minds in that insight.

Our habits of grasping for things to be permanent, singular, or inherently existing are extremely powerful. We must gain and develop genuine experiences of the truth of the impermanence, interdependence, and emptiness (the fact that “things” are not as substantial as they seem) to overcome those powerful habits. The only way to develop our intellectual understanding into the experience and realization is by resting single-pointedly in Vipassana by the power of Calm Abiding. That gets to the root of things so that the weeds won’t grow back. (Watch Khen Rinpoche share about the importance for cultivating awareness in this short clip from our Shamata Retreat 2021.)

It is the combination of a regular Shamata and Vipassana meditation practice that helps us live from a truer perception of reality; the reality that we are all a part of the great ocean of awareness. We learn to see the whole ocean, not just the surface waves. That ocean (including, but not only, the waves) is the true source of all happiness, and a freedom from suffering. This is the goal of meditation we’ve all long sought. With these methods, we can make real progress toward that goal—our true home.